September 28, 2016

By Sally Greenberg

Nearly eight years after the Great Recession, where unscrupulous lending practices brought our global economy to a breaking point, we’ve learned that the Big Banks have learned little since the meltdown and returned to business as usual.

The latest culprit is Wells Fargo, where an investigation by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau uncovered a fraudulent debit and credit card scam affecting millions of unwitting Wells Fargo customers. The executive who oversaw this rapacious operation, Carrie Tolstedt, announced over the summer she is retiring with a reported package of $124 million, and Wells Fargo has failed to hold anyone at the top responsible, while firing more than 5,000 of the workers who were forced to participate in this illegal activity.

And yet, this incident is not the first time we’ve seen the largest financial institutions game the system since the Great Recession. In recent years, Wells Fargo and other large banks have been fined and faced lawsuits and investigations regarding financial violations and misuse of ordinary Americans’ money.

How can this still be happening? In the eight years since the financial crisis, dozens of Congressional hearings, thousands of news stories, a host of best-selling books, and a blue ribbon commission promised to help us understand what went wrong and how to prevent a recurrence. The Dodd-Frank Act became law amidst much fanfare – and opposition. But since then, the nation’s biggest banks including Wells Fargo, have only gotten bigger, and as this newest episode demonstrates, old habits die hard.

Today, almost eight years later, the six largest U.S. financial institutions now have assets of some $10 trillion – that’s more than half of our nation’s GDP. Yet, against this backdrop of stratospheric growth, Wells Fargo has shown that nothing has changed and their leadership continues to look for ways to maneuver around the rules to drive profit. Importantly, these large financial institutions, now, would like to take over the secondary housing market. Already the largest mortgage lending bank in the nation, Wells Fargo has spent more than $20 million in the last few years lobbying Congress to replace mortgage backers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with – you guessed it – a more bank-centric model. Ironically, it was Wells Fargo that settled with the Department of Justice for $335 million over charges that it sold fraudulent loans to Fannie and Freddie.

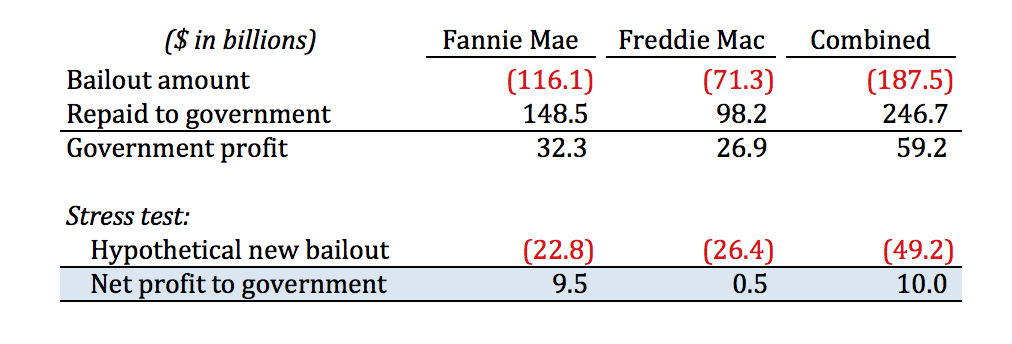

Here are the facts: in the years since the global financial crisis, significant reforms to Fannie and Freddie have allowed them to become profitable again and repay $187 billion to the Treasury Department, plus another $60 billion in dividend payments. Still, some say that Fannie and Freddie not only caused the crisis, but are emblematic of big government cronyism and demand they be dismantled. Others say the two government-sponsored enterprises have helped tens of millions of Americans achieve the American Dream of homeownership and create wealth for future generations. So far, no one has come up with an acceptable alternative for keeping the nation’s mortgage market liquid and stable enough so qualified, creditworthy buyers can obtain sustainable long-term home loans.

The most common-sense solution is to continue reforming Fannie and Freddie, allow them to retain earnings and rebuild their capital base, and protect taxpayers against future bailouts. The most reckless decision would be to hand over their business to Wells Fargo or some of its big-bank peers and let them gamble away our future. Hopefully, policymakers have learned from the age-old idiom, “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” – with the latter only hurting working Americans’ ability to achieve long-term economic security.

Sally Greenberg is executive director of National Consumers League.